I am ushered into an eerily silent room, roughly the size of a cathedral, where everything is gleaming white and pristine. In front of me is a white desk that has been carefully placed in the middle of the room. The door snaps shut behind me with a metallic clang that temporarily disturbs the unnatural quiet of the place. From the far end of the room, a woman frowns at me from behind her own white and immaculate desk. She is the keeper of the archives and I have disturbed her peace, but more importantly I am about to disturb her precious and mysterious archival material, held hostage behind the many closed and locked doors that surround me. However, first I must pass her test in order to gain entry and view the material she guards so fiercely. As I walk towards her I can see that she is thinking how unexpected and unacceptable it is for a university student such as myself to dare to request to use the archives. She looks me up and down before silently turning me away, pointing back towards the door I entered through, which has suddenly re-opened. The test is over already. I have failed. It is widely known that archives are not for the use of students, and that they are reserved strictly for … actually, who is allowed to visit and view archival material?

It is a common misconception amongst university students of all levels that archives are places reserved only for academics, historians, and other seriously clever people who belong to secret societies that are run by even cleverer people. If you are a student, you are an academic, you are an historian, and you are certainly an intelligent individual. There is no secret society, there is no test, and not only are you allowed to access archival material of all kinds, you should feel comfortable doing so. It may be the age, state, or status of the literature and material housed in archives that helps to perpetuate the myth that you must be a senior member of Mensa (at the very least) to access this information. Whilst arguably the main point of archives is to preserve the material and/or information it contains for future generations, there is very little point in preserving something for future use and denying access to those who wish to view and access the material in the present. Whilst it is true that archival material must be carefully and respectfully handled, I cannot stress too much that such care is taken not to discourage potential visitors from accessing the material, but in order to enable others to view, handle, study, and enjoy it in the future. Archives are not terrifying or elitist places. From my own personal experience working in Special Collections in The Sheppard-Worlock Library (under the guidance of the extremely friendly and helpful librarian, Karen Backhouse), archives are fascinating treasure troves of information which can be enjoyed by all who desire access to the material and information within.

My first real experience of handling archival material was in February 2016. I was in the final year of my MA course in Popular Literatures, and in the preliminary stages of research for my dissertation on Charlotte Brontë’s early fiction, or juvenilia, as it is more commonly known. Following a seminar about different types of research, my class were invited into Special Collections to view some material and introduce us to the possibility of archival research, something which I had never thought much about due to the myth that only certain types of people were allowed into literary archives. However, following the class, in which Karen had stressed the fact that access to Special Collections is available to all Hope students, I began to think more seriously about archival research, which, due to the obscurity of my topic, seemed like a good idea as much of Brontë’s early fiction is notoriously difficult to access in print.

The following day, I emailed Karen to enquire about the possibility of volunteering in the department for a few hours a week in order to gain some experience and learn more about archival research due to the possibility of a visit to view some of Brontë’s original manuscripts as part of my dissertation research. Karen kindly offered me some voluntary work, and during those few hours that I spent in Special Collections every week, I learnt so much about both archival work and more general library work, and I sincerely hope that I was of some use to Karen. My duties included assisting in identifying material in the Radcliffe early printed collection that required boxing as part of the on-going preservation programme, assisting in the digitalization of a music manuscript, processing and cataloguing donated stock by their unique classification system, updating online bibliographic records, and hoovering (yes, hoovering!) some of the older books in the department.

Following a few months’ work in the department, I decided to arrange to view some of Brontë’s original manuscripts. Although these manuscripts are now scattered throughout the world, many remain in the UK, housed in private collections, but also in institutions such as the British Library, and the Brontë family’s former home, the Brontë Parsonage Museum.

It was thanks to Karen’s time and kindness that I eventually felt comfortable handling rare material, and had finally arrived at the realisation that I was permitted to view archival material related to my subject if I desired to do so. Following communication with the Curator of the Brontë Parsonage Museum, Sarah Laycock, I was invited to view Brontë’s original manuscripts and letters as part of my dissertation research. Due to the nature of the material I would be handling, I was required to produce an academic reference in order to visit, and also to demonstrate that I had some familiarity with handling archival material, which due to Karen’s kindness, I already had. My visit was fascinating; not only was Sarah kind and welcoming, I finally got to view and handle the texts I had been studying so much and fascinated by for so long. Going into the Brontë archive, I was confident about handling the materials despite their age and size.

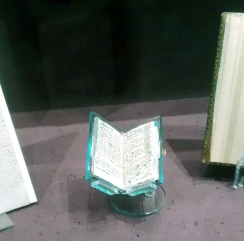

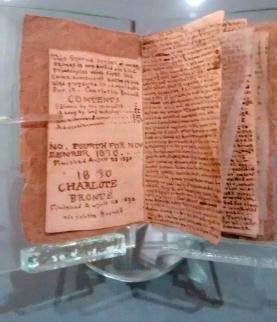

A significant portion of Brontë’s surviving juvenilia is tiny in size, and, despite my training, it was quite difficult to handle, which is why previous experience in the handling of archival material was required. These texts are affectionately and unofficially known as the Brontës’ tiny books (Charlotte’s brother, Branwell, also contributed to the Glass Town and Angrian saga, the same childhood fictional world as his sister). Handling the texts gave me an entirely new perspective on the literature contained within and served as a reminder that whatever the later texts consisted of, the origins of this fictional world were the result of child’s play and the childhood games of precocious siblings, echoes of which can be traced throughout Charlotte’s adult novels, including The Professor, and Jane Eyre.

Following my visit to the Brontë Parsonage Museum, my perception of Brontë’s early fiction altered, and my dissertation began to take shape. Although it subsequently altered many times before the submission deadline, without Karen’s time and patience in teaching and familiarizing me with archival procedure, I would still be struggling to imagine exactly what the Brontës’ juvenilia meant to them and to understand and appreciate the circumstances surrounding its production and survival. Sometimes you cannot simply read a text, you must experience it, and for me, this is the main benefit of archival research. Once again I would like to thank Karen for her help and advice in the archives and encourage you to pay her a visit if you are considering archival research for a project. My time in the Special Collections really did alter my way of thinking about my material; it can do the same for you too.

“All photos were taken by myself or a relative and appear with the kind permission of the Brontë Society”

By Nicola Friar

May 2017